Spotlight Archive

One hundred years ago this June, Pope Pius X issued Sapienti Consilio, ending the United States’ status as a missionary territory under the jurisdiction of the Propaganda Fide (later the Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples). The Church in the United States had passed from childhood to maturity, thanks in large measure to the extraordinary labors of the missionaries who tamed America’s religious wilderness.

In many cases, missionaries and explorers accompanied each other into the New World. Spanish Franciscans and Jesuits were among the first Europeans to encounter the native peoples of the American South and West, while French Jesuits were similarly early figures in the settlement of the St. Lawrence Valley and the Great Lakes region. In some cases, their intent to evangelize met with little success. Jesuit Juan Segura died in Virginia in 1571.The Georgia Martyrs were six Franciscans killed near the Atlantic coast in 1597. Isaac Jogues and the rest of the North American Martyrs were put to death by Iroquois in the 1630s and forties.

Sébastien Râle successfully ministered to the Abenakis in Maine, but his work was terminated at the hands of a war party from New England. Eusebio Kino also enjoyed some success among the Pimas of the Southwest, but his effort, too, was cut short by violence.

The paucity of Catholics in British North American made it missionary territory as well. Father Andrew White was known as the “Apostle of Maryland,” though the marginalization of Catholics there, too, forced him out of the country. As the colonial period drew to a close, the missionary task became less dangerous if no less difficult. Father Ferdinand Farmer was one of the best known priests of the Revolutionary Era, serving a dispersed population of Catholics in New York, New Jersey, and eastern Pennsylvania.

Many missionaries exerted a lasting impact not only on the history of the Church in the United States, but on the development of the nation itself. Jesuit Jacques Marquette accompanied Louis Joliet on his exploration of the Missisippi River, opening up the region to French settlement. He traveled widely in the future states of Michigan, Wisconsin, and Illinois.

Many missionaries exerted a lasting impact not only on the history of the Church in the United States, but on the development of the nation itself. Jesuit Jacques Marquette accompanied Louis Joliet on his exploration of the Missisippi River, opening up the region to French settlement. He traveled widely in the future states of Michigan, Wisconsin, and Illinois.

Elsewhere in Michigan, Fr. Gabriel Richard contributed immensely to the progress of the city of Detroit, and he his honored as one of its founders. Frederic Baraga was active throughout Michigan and became the first bishop of its Upper Peninsula. Stephen Badin traversed Kentucky and Ohio in the early 1800s, helping to grow the Church in the Ohio Valley. Elizabeth Seton’s Sisters of Charity, a new American congregation, also contributed significantly to the development of the region.

Demetrius Gallitzin and Henry Lemke encouraged Catholic settlement of western Pennsylvania: towns such as Latrobe, Loretto, and Carrolltown owe their existence to these missionary priests.

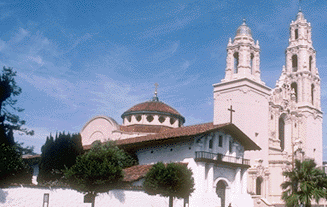

Meanwhile, in the West, Franciscans Junípero Serra and Fermín Lasuén orchestrated the foundation of a chain of missions in California that provided the geographical template upon which the state would grow. Their missions are reflected in the Golden State’s municipal nomenclature: San Diego, Santa Cruz, Santa Clara, San Francisco.

Meanwhile, in the West, Franciscans Junípero Serra and Fermín Lasuén orchestrated the foundation of a chain of missions in California that provided the geographical template upon which the state would grow. Their missions are reflected in the Golden State’s municipal nomenclature: San Diego, Santa Cruz, Santa Clara, San Francisco.

Farther north, Pierre deSmet, SJ brought Catholicism to a wide expanse of land in the plains and mountains. He worked among Coer d’Alenes, Sioux, and Blackfeet. Mother Frances Cabrini’s Missionary Sisters of the Sacred Heart was one of the earliest women’s congregations active in the Midwest and West. Missions among Native and African Americans were promoted by Dominican Samuel Mazzuchelli, the Josephite fathers, and St. Katharine Drexel and her Blessed Sacrament Sisters.

By the time Pius removed the country’s mission status, the American Church had already begun producing missionaries of its own for the spreading of the faith in other lands.

The first American missionaries to “foreign” lands were those who labored in territories that would later become part of the United States, such as Bl. Damien and Bl. Marianne Cope in Hawaii. The Propaganda Fide assigned the Bahamas first to the Diocese of Charleston and later to New York.

The first American missionaries to “foreign” lands were those who labored in territories that would later become part of the United States, such as Bl. Damien and Bl. Marianne Cope in Hawaii. The Propaganda Fide assigned the Bahamas first to the Diocese of Charleston and later to New York.

In 1852, the Congregation of Holy Cross sent the first Americans to India, and in 1890, Daughter of Charity Xavier Berkeley arrived in China. By 1908, there were seventy American religious working in foreign missions.

Venerable orders such as Franciscans and Jesuits sent missionaries to many places, including China. The Society of the Divine Word, an important missionary congregation, was centered at Techny, Illinois, where their companion female congregation, the Holy Spirity Missionary Sisters, was established in 1901. The Divine Word fathers went to China in 1919 and to New Guineau in 1926. Many orders were forced out of China during its mid-century strife; the Sisters of Divine Providence shifted their efforts to Korea, which became another important mission venue. The first American sisters to venture to South America were the Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, who landed in Lima, Peru in 1922.

One new American order had missions as its sole purpose. Popularly named after its founding site at Maryknoll, New York (1911), the Catholic Foreign Mission Society became active throughout Latin America, Africa, and Asia. The Columban Fathers (1920) and Columban Sisters (1930) were also devoted to missionary activity. By 1940, there were more than 2200 American Catholics serving in foreign missions.

A number of American Catholic institutions served the missionary cause. The Catholic Church Extension Society, founded in 1905, promoted the work of missions in remote ares of the United States. Periodicals such as The Field Afar, The Shield, and Catholic Missions reported on and helped to raise support for actitivities abroad. The Conference of Catholic Bishops supplied aid through the US Mission Secretariat (1949) and its successor agencies, the US Catholic Mission Council (1970) and the US Catholic Mission Association (1982).

The character of mission activity has changed over the years. As a series of popes urged attention to the matter (Benedict XV, Maximum Illud, 1919; Pius XI, Rerum Ecclesiae, 1926; Pius XII, Evangelii Praecones, 1951), missionaries focused on cultivating native clergy and religious. The Sisters of Loretto, Sisters of Providence, and Maryknoll Sisters were among the first to establish such congregations in the regions they served. In the fifties and sixties, when Archbishop Fulton Sheen headed the Society for the Propagation of the Faith, missionaries were viewed in part as a bulwark against the spread of Communism, but that concern waned as the motivating ideas of missionaries’ changed and the Cold War eventually drew to a close. In 1950, the formation of the St. James Society reflected the inauguration of significant missionary activity on the part of diocesan clergy. Lay missionaries, too, began to flourish in the 1950s; among their organizations were the Lay Mission Helpers of Los Angeles, The Grail, and the Papal Volunteers for Latin America.

The same decades saw the opening of new mission lands as Africa became the site of many Catholic missions. The Holy Ghost Fathers and the Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary were pioneers in the evangelization of that continent.

The same decades saw the opening of new mission lands as Africa became the site of many Catholic missions. The Holy Ghost Fathers and the Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary were pioneers in the evangelization of that continent.

Native-born missionaries continue to be sent forth from the United States to other nations. In 1992, there were almost 5500 American Catholic missionaries working abroad, 1300 of them in Latin America. Besides the congregations already mentioned, the School Sisters of Notre Dame and the Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet are among the most numerous of missionary religious. The physical danger courted by the New World’s early missionaries persists: reports of the violent deaths of American priests and nuns in the past decade have come from Asia, Africa, and Latin America.

Yet the contours of mission activity are ever shifting. The 1986 statement from the American bishops, To the Ends of the Earth, affirmed the continuation of mission work but it also noted that "every local church is both mission-sending and mission-receiving." In many dioceses, priest shortages have led bishops to invite foreign priests to serve American parishes, and many of these priests hail from South America, Asia, and Africa—the very places evangelized by Jesuits, Maryknollers, and other American missionaries earlier in the twentieth century.

©2008 CatholicHistory.net. Posted June 3, 2008.

Photos, from top: Father Marquette; Mission San Francisco, © CatholicHistory.net; Our Lady of Sorrows Church, Molokai, constructed by Bl. Damien, 1874, courtesy National Archives and Records Administration (unrestricted); French West Africa, courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration (unrestricted).

Sources and Further Reading

Angelyn Dries, OSF, "American Catholic Missionaries (Abroad)"; Robert Trisco, "English Missions in Colonial America"; Charles Edwards O'Neill, "French Missions in Colonial America"; and Stafford Poole, CM, "Spanish Missions in Colonial America"; in .