Spotlight Archive

November is election month in the United States. As this year’s political activity draws to a close, anticipation of next year’s presidential race ratchets up a notch. The questions surrounding Republican front-runner Rudy Giuliani’s Catholic faith recall the boisterous history of Catholics in American politics.

In most of the colonies through most of early American history, Catholics were barred from participating in the political process. At the time of the Revolution, however, Catholics began taking an active part in political affairs. Charles Carroll was an early champion of independence and the only Catholic signer of the Declaration of Independence. In the formation of the new nation, Catholic patricians Daniel Carroll and Thomas Fitzsimons represented their states of Virginia and Pennsylvania at the constitutional convention and both signed the resulting Constitution.

In most of the colonies through most of early American history, Catholics were barred from participating in the political process. At the time of the Revolution, however, Catholics began taking an active part in political affairs. Charles Carroll was an early champion of independence and the only Catholic signer of the Declaration of Independence. In the formation of the new nation, Catholic patricians Daniel Carroll and Thomas Fitzsimons represented their states of Virginia and Pennsylvania at the constitutional convention and both signed the resulting Constitution.

Initially a small minority, Catholics gained political clout as their numbers increased with immigration after 1840. Strong concentrations of Catholics in New England and parts of the Midwest made those regions natural springboards for Catholics with political aspirations. Catholic politicians in the antebellum era included Edward Kavanaugh of Maine; William Gaston of North Carolina; and George Pugh of Ohio. After the Civil War, James Shields served as US Senator from three different states (Illinois, Minnesota, and Missouri), the only American to have done so.

By 1890, most major cities had significant Catholic political influence, many in the form of Irish mayors. William Russell Grace was the first Catholic mayor of New York City (1880–188). Some Catholic administrations were notorious for patronage and nepotism: the reign of James Curley in Boston was a prime example.

On most of the nineteenth century’s political issues—from temperance and tariffs to slavery and suffrage—Catholics could be found on both sides of the debate. Catholic women such as Teresa Crowley and Lucy Burns were active suffragists. After the nineteenth amendment was enacted in 1918, Catholic women entered politics in significant numbers. The first Catholic congresswoman was Mae Hunt Nolan, who represented California. Later, Kathryn Granahan would serve as a US Representative from Pennsylvania and Treasurer of the United States; Clare Boothe Luce was a Congresswoman and Ambassador to Italy; and Jane Hoey was appointed the first director of the Bureau of Public Assistance in the Social Security Administration.

Charles O’Conor was the first Catholic candidate for president, though his third-party campaign in 1872 hardly registers as memorable. The first time Catholicism played a major role in a presidential election, it was by negative influence. In 1884, Republican James Blaine accused Democrat Grover Cleveland of being beholden to a party of “rum, Romanism, and rebellion,” packaging together the three great fears of the Protestant nativists.

The American bishops elicited a mixed chorus of praise and criticism when in 1919 they issued a statement widely perceived to be supportive of progressive politics. Their national organization, the NCWC, would henceforth be a significant presence in Washington.

The American bishops elicited a mixed chorus of praise and criticism when in 1919 they issued a statement widely perceived to be supportive of progressive politics. Their national organization, the NCWC, would henceforth be a significant presence in Washington.

The history of Catholics and politics came to a head in 1928, when New York governor Al Smith won the Democratic nomination for president. Some non-Catholics asked legitimate questions about the relationship between church and state, but the honest inquiries were drowned in a prejudiced campaign of Catholic baiting and fearmongering. It remains debatable whether Smith lost the general election because of his Catholicism or other factors, but religion certainly played a role. Catholics were disheartened but defiant. Paulist priest James Gillis, editor of The Catholic World, summed up the view of many: “We shall not wither up and blow away.”

In fact, Smith’s defeat marked the beginning rather than the end of heavy Catholic political participation. Occasionally, the question of clerical involvement in politics surfaced. Father Gabriel Richard was the first priest to serve in Congress, representing the Territory of Michigan in 1823. Radio priest Charles Coughlin, enormously popular in some circles, provoked much opposition for his direct campaign against President Roosevelt in the 1930s. In the 1970s, Jesuit Robert Drinan also stirred controversy, both for being a priest-congressman and for his position on abortion legislation. Priests have served with less opposition in non-elective office: John Ryan and Francis Haas both filled various posts under the Franklin Roosevelt Administration. Ryan and Haas joined other priests such as Charles Rice in actively supporting the American labor movement. The Association of Catholic Trade Unionists gave Catholics a voice in that important political force.

Religious sisters, too, have engaged political life, though their participation has also been contentious. Following a controversy over abortion, Agnes Mary Mansour decided to leave the Sisters of Mercy and retain her position as the State of Michigan’s director of social services. Two other Sisters of Mercy, Elizabeth Morancy and Arlene Violet—both involved in Rhode Island election campaigns—also opted for political over religious life when compelled to choose.

Catholic influence in politics in the post-World War II era was especially noteworthy for its anti-Communism. Most famous in this connection was Wisconsin Senator Joseph McCarthy, though other Catholics such as Jesuit Edmund Walsh and Sulpician John Cronin played important if less spectacular roles.

It was only a matter of time before another Catholic was nominated for a major party nomination. When John F. Kennedy became the Democratic candidate in 1960, some familiar objections appeared. Kennedy was forced to justify his religious views and did so most famously in a speech to the Greater Houston Ministerial Association. Times had changed since 1928, though, and, while anti-Catholicism was not absent from the campaign, other issues took precedence. Most prominent Protestant spokesmen disowned the nation’s anti-Catholic past.

It was only a matter of time before another Catholic was nominated for a major party nomination. When John F. Kennedy became the Democratic candidate in 1960, some familiar objections appeared. Kennedy was forced to justify his religious views and did so most famously in a speech to the Greater Houston Ministerial Association. Times had changed since 1928, though, and, while anti-Catholicism was not absent from the campaign, other issues took precedence. Most prominent Protestant spokesmen disowned the nation’s anti-Catholic past.

By the 1960s, Catholics were firmly entrenched in the nation’s political scene. The first Catholic Speaker of the House was Massachusetts Democrat John McCormack, after whom it became almost customary for the postition to be held by an Irish Catholic; later figures included Tip O’Neill and Tom Foley. Catholics figured prominently in the conservative movement, boasting such names as William F. Buckley, Jr. and Michael Novak. They were also leaders in leftist political activism, counting among their number pacifists and anti-war stalwarts such as Dorothy Day, Fathers Daniel and Philip Berrigan, and Michael Harrington.

As with suffrage, Catholics were active on both sides of another political battle involving women, the Equal Rights Amendment. Dorothy Shipley Grainger, founder of the St. Joan Society for Catholic Women was an active proponent of the ERA in its earlier version in the 1940s. In the 1970s and eighties, Phyllis Schlafly spearheaded opposition to the amendment.

After 1973, abortion became the preeminent political issue for many Catholics. Although Catholics had voted overwhelmingly Democrat since at least the time of Al Smith, that party’s defense of abortion rights and the changing socio-economic status of Catholics effected a transfer of the loyalties of many Catholics toward Republican politics. Pennsylvania governor Robert Casey, Sr., well-known as pro-life and Catholic, was denied a speaking platform at the Democratics Convention in 1992, confirming the shift. At the same time, the bishops of the country, through their national organization (now the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops), continued to advocate social and economic policy prescriptions more in line with the Democratic Party platform, and the Catholic vote was often split evenly between the two major parties.

After 1973, abortion became the preeminent political issue for many Catholics. Although Catholics had voted overwhelmingly Democrat since at least the time of Al Smith, that party’s defense of abortion rights and the changing socio-economic status of Catholics effected a transfer of the loyalties of many Catholics toward Republican politics. Pennsylvania governor Robert Casey, Sr., well-known as pro-life and Catholic, was denied a speaking platform at the Democratics Convention in 1992, confirming the shift. At the same time, the bishops of the country, through their national organization (now the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops), continued to advocate social and economic policy prescriptions more in line with the Democratic Party platform, and the Catholic vote was often split evenly between the two major parties.

In an ironic turn of events, when the next Catholic candidate for president, John Kerry, appeared in 2004, the “Catholic issue” involved questions not about Kerry’s ability to differentiate his religious beliefs from his political duties but questions about whether Kerry was “Catholic enough” on the matter of abortion. The involvement of Catholic bishops in the campaign of 2004 generated controversy not because they defended the Catholic candidate against anti-Catholic slurs but because they criticized him for not upholding the teachings of the Church. The relationship between Catholics and American politics had come full circle.

©2007 CatholicHistory.net. Posted November 7, 2007.

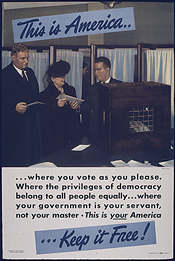

Photos, from top: Charles Carroll, courtesy of USHistory.org; Franklin Roosevelt and Al Smith, courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration (unrestricted); John F. Kennedy, courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration (unrestricted); World War II-era poster, courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration (unrestricted).

Sources and Further Reading

T. Sarbaugh, "Politics and American Catholics," and J. Kenneally, "American Catholic Women,"