Spotlight Archive

In recent months, controversy has swirled around Catholic hospitals in Connecticut and Denver over the provision of abortion and contraception. The high stakes of these disputes point to the central role that Catholic individuals and institutions have played in the history of health care in the United States.

Charitable care for the sick has been a major part of the mission of many religious orders for centuries. As religious congregations entered the United States, they brought this dimension of their work along. Female communities in particular contributed to the building of health care facilities and furnished the personnel to staff them.

The Ursulines worked in a hospital in New Orleans in the eighteenth century, before the region was a part of the United States. Elizabeth Ann Seton’s Sisters of Charity became the first to staff an American hospital, the Baltimore Infirmary (later the Hospital of the University of Maryland), in 1823. Sisters of Charity also served the first Catholic hospital, founded by Irish-American millionaire, John Mullanphy, in St. Louis in 1828. Initially a three-room log cabin, Mullanphy funded the construction of a modern brick building to house the new hospital.

The Ursulines worked in a hospital in New Orleans in the eighteenth century, before the region was a part of the United States. Elizabeth Ann Seton’s Sisters of Charity became the first to staff an American hospital, the Baltimore Infirmary (later the Hospital of the University of Maryland), in 1823. Sisters of Charity also served the first Catholic hospital, founded by Irish-American millionaire, John Mullanphy, in St. Louis in 1828. Initially a three-room log cabin, Mullanphy funded the construction of a modern brick building to house the new hospital.

Sister of Charity Mother Angela Hughes, who served for a time at Mullanphy’s hospital, went to New York to found another early hospital, St. Vincent’s. Hughes was the younger sister of Bishop John Hughes of New York.

Besides the Sisters of Charity’s five hospitals (including St. Louis and St. Vincent’s), other early nursing congregations and their hospitals included the Sisters of Mercy in Pittsburgh; the Sisters of St. Joseph in Philadelphia; and the Sisters of Charity of Nazareth in Kentucky and Tennessee.

Catholic hospitals were often among the first institutions established on the western frontier. Bishop Blanchet of Nesqually, Washington, invited the Sisters of Charity of Providence to the Northwest in 1856, to staff a hospital at Fort Vancouver. Mother Joseph Pariseau worked together with Protestant and Jewish women to build and furnish the infirmary. By the time of her death in 1902, there were eleven hospitals in Washington and Oregon. Pariseau’s importance to the development of the region was recognized by her being selected as one of the figures representing Washington in the U.S. Capitol’s Statuary Hall.

In 1924, another monument to Catholic sisters was erected in Washington: a bas-relief honoring their extensive service on both sides of the Mason-Dixon during the Civil War. Six hundred seventeen sisters from twenty-one congregations made up some twenty percent of the conflict’s nursing corps.

Less auspicious was the contribution of Dr. Samuel Mudd, a Maryland Catholic who treated the wounded John Wilkes Booth following his assassination of President Lincoln. Mudd was convicted as a conspirator, imprisoned, and then pardoned by President Andrew Johnson.

The growth of Catholic health care mirrored the growth of the nation. In 1872, there were about 75 Catholic hospitals; by 1910 there were 400. The increase reflected also Catholic participation in the professionalization of medicine in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In Springfield, Illinois, where the Hospital Sisters of St. Francis ran St. John’s Hospital, they founded the first Catholic nursing school in 1886.

The growth of Catholic health care mirrored the growth of the nation. In 1872, there were about 75 Catholic hospitals; by 1910 there were 400. The increase reflected also Catholic participation in the professionalization of medicine in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In Springfield, Illinois, where the Hospital Sisters of St. Francis ran St. John’s Hospital, they founded the first Catholic nursing school in 1886.

Catholic immigration brought new religious congregations. Mother Frances Cabrini and her Sisters of the Sacred Heart founded New York’s Columbus Hospital in 1892, and spread across the country, with foundations in Chicago and Seattle.

The Catholic Hospital Association (CHA) held its first convention in 1915, by which time there were 220 Catholic nursing schools. The organization was an indication of the increasing standardization of American medicine and education, but would also become a marker of Catholic efforts to maintain a distinct identity in the face of the secularization of American institutions.

Medical doctors have been prominent among the Catholic laity in America. Dr. James J. Walsh became well known for his writings on Church history, including the best-selling The Thirteenth, Greatest of Centuries (1907). Later, Dr. Thomas Dooley’s humanitarian and anti-Communist activities in southeast Asia, reported in Deliver Us from Evil (1956), made him an American celebrity.

Doctors shared in the organizational trends of the early twentieth century. The first Catholic physicians guild was founded in Boston in 1912. In the 1930s, the head of the Brooklyn guild, Dr. R.A. Rendick, spearheaded the formation of a national organization with which the various local guilds could affiliate. The National Federation of Catholic Physicians Guilds (NFCPG) inaugurated its publication, the Linacre Quarterly, at the same time. In 1944, the organization moved to St. Louis, operating in close cooperation with the CHA. By 1948, there were eleven member guilds.

Catholic institutions often reflected the social patterns of American society. Through the 1920s, the overwhelming majority of Catholic hospitals were segregated with separate wards for black patients. Yet Catholics were also in the forefront of racial progress: When Archbishop Joseph Ritter desegregated St. Louis parochial schools in 1948, the mandate included nursing schools. In 1953, St. Vincent’s in Kansas City became the first integrated American hospital with black physicians on staff.

Catholic institutions often reflected the social patterns of American society. Through the 1920s, the overwhelming majority of Catholic hospitals were segregated with separate wards for black patients. Yet Catholics were also in the forefront of racial progress: When Archbishop Joseph Ritter desegregated St. Louis parochial schools in 1948, the mandate included nursing schools. In 1953, St. Vincent’s in Kansas City became the first integrated American hospital with black physicians on staff.

The NFCPG peaked in the 1960s at 10,000 physician members in more than 100 associated guilds. But divisive issues loomed. The political and social controversies of the 1960s had an enormous impact on Catholic health care providers. In 1965, the CHA endorsed government socialization of medicine, a move staunchly opposed by the NFCPG. The latter organization separated from the CHA and moved its offices to Milwaukee. By that time, an even more explosive issue had landed amidst Catholic health professionals: birth control.

Ironically, it was a Catholic doctor who helped to bring the issue of artifical contraception to the center of America’s culture wars. Dr. John Rock was one of the developers of the birth control pill, approved by the FDA for use in the United States in 1960. A regular Mass-goer, Rock believed that the Church would approve the use of the pill for contraceptive reasons. He became the public face of the Pill in American culture, appearing on TV and in major news magazines.

Ironically, it was a Catholic doctor who helped to bring the issue of artifical contraception to the center of America’s culture wars. Dr. John Rock was one of the developers of the birth control pill, approved by the FDA for use in the United States in 1960. A regular Mass-goer, Rock believed that the Church would approve the use of the pill for contraceptive reasons. He became the public face of the Pill in American culture, appearing on TV and in major news magazines.

A 1964 meeting co-sponsored by the NFCPG and the National Conference of Catholic Bishops' Family Life Committee intimated the battles to come. The physicians’ group objected to a letter proposed by the Committee to urge Pope Paul VI to declare contraceptive use morally licit. The ensuing struggle effectively ended the close cooperation between the bishops conference and the NFCPG. The doctors’ group itself split over the issue following the pope’s 1968 encyclical condemning birth control. Infighting led to declining membership and the fading of local guild activity. By 1997, most of the local guilds had dissipated and the organization was renamed the Catholic Medical Association.

Despite facing the challenges of declining numbers of religious sisters, increasing competition and government regulation, and rising costs of personnel and technology, Catholic hospitals remain a large provider of health care in the United States. Present in all fifty states, Catholic facilities account for more than one-fifth of all admissions in twenty of those states. Nationally, one recent year's Catholic hospital admissions totalled 5.4 million patients, plus more than 15.4 million emergency room visits and 86 million outpatient visits. More significant than sheer numbers, the legacy of Catholic health care providers—from frontier medical stations to Civil War field hospitals to modern health care campuses—is their witness to the Church's perennial commitment to care for those in need with compassion and respect.

©2007 CatholicHistory.net. Posted February 1, 2007.

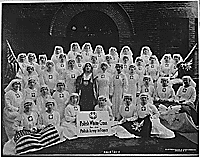

Photos from top: St. Anthony's Hospital, Terre Haute, IN; Polish nurses, World War II; Loretto Hospital, New Ulm MN; Pope Paul VI; all courtesy National Archives and Records Administration, unrestricted.

Sources and Further Reading

Christopher Kauffman, “Catholic Health Care,”

Thomas J. Shelley, “Angela Hughes,”

Karen M. Kennelly, CSJ, “Women Religious in America,”