Spotlight Archive

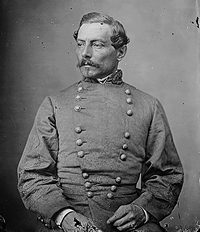

One hundred fifty years ago this February, Louisiana Catholic P.G.T. Beauregard resigned his commission with the US Army and joined the Confederacy. The divisions wrought by the Civil War affected all Americans, Catholics included.

One hundred fifty years ago this February, Louisiana Catholic P.G.T. Beauregard resigned his commission with the US Army and joined the Confederacy. The divisions wrought by the Civil War affected all Americans, Catholics included.

The Irish and German immigrants who swelled the Catholic population of the United States concentrated in the North; thus Catholics were far more numerous in the states—and the armies—of the Union. Religious identities were sometimes reflected in the organization of units: New York’s “Fighting 69th” was one of the war’s most famous regiments, and one of its most Catholic.

Even so, Catholics were among those who vehemently opposed the war and its aims. In political terms, the war was seen as a project of Republican Abraham Lincoln, whom the country’s predominantly Democratic Catholics mistrusted. In economic terms, Catholic Irish in particular were more concerned with scrambling onto the bottom rung of the nation’s ladder of economic opportunity than with adding a vast new pool of free black laborers to compete for the low-skilled jobs of the service and manufacturing sectors. Irish Catholic opposition to the war reached a boiling point in 1863, when an attempt by the Administration to enforce compulsory military service set off the New York Draft Riots.

For these and other reasons, most Americans perceived abolitionism to be a Protestant phenomenon; few Catholic leaders were active in the movement. In the South, prominent bishops such as John England of Charleston attempted to walk the fine line between Rome’s increasingly vocal opposition to slavery (Pope Gregory XVI issued a ringing condemnation of the slave trade in 1839, which many read as implying denunciation of slavery itself) and the need to demonstrate loyalty to the southern culture of which they were a part.

For these and other reasons, most Americans perceived abolitionism to be a Protestant phenomenon; few Catholic leaders were active in the movement. In the South, prominent bishops such as John England of Charleston attempted to walk the fine line between Rome’s increasingly vocal opposition to slavery (Pope Gregory XVI issued a ringing condemnation of the slave trade in 1839, which many read as implying denunciation of slavery itself) and the need to demonstrate loyalty to the southern culture of which they were a part.

England’s successor, Bishop Patrick Lynch, exchanged a series of published letters with Archbishop John Hughes of New York in 1861. Both men displayed their fidelity to their respective regions. Hughes was pro-union and supported emancipation. Lynch perceived the conflict to be instigated by radicals in the North, such as the “Black Republicans” who promoted racial equality and the political program of Abraham Lincoln. Bishop Martin Spalding of Louisville was one of the more forthright slavery apologists among the Catholic leadership, publishing a defense of the "peculiar institution" in 1863. In contrast, Bishop James Whelan of Tennessee, refusing to be party to secession, resigned his see and moved north.

African-American Catholics might be expected to be anti-slavery and pro-Union, but they were very few in the North and exerted little influence in the Church or the abolitionist movement. In Louisiana, however, black Catholics helped to form three regiments of Union soldiers. These Afro-Creoles were ministered to by a French-born chaplain, Claude Paschal Maistre, in direct defiance of his superior, New Orleans archbishop Jean-Marie Odin. One of these Louisiana Catholics, Andre Cailloux, was the first black soldier to die in combat.

Of the southern states, only Louisiana and Maryland had significant Catholic populations, and Beauregard represented the former in the South’s military leadership. General James Longstreet was not Catholic at the time of the war, but he joined the Church afterward (1877). Other Catholics included Major General William Whiting, Admiral Raphael Semmes, and Confederate Secretary of the Navy, Stephen Mallory. As in the North, there were predominantly Catholic ethnic regiments, such as the Irish 8th Alabama.

Of the southern states, only Louisiana and Maryland had significant Catholic populations, and Beauregard represented the former in the South’s military leadership. General James Longstreet was not Catholic at the time of the war, but he joined the Church afterward (1877). Other Catholics included Major General William Whiting, Admiral Raphael Semmes, and Confederate Secretary of the Navy, Stephen Mallory. As in the North, there were predominantly Catholic ethnic regiments, such as the Irish 8th Alabama.

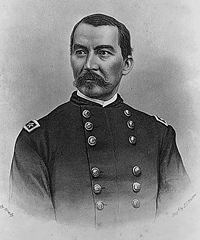

On the Union side, Catholic officers included Colonel Patrick Guiney, who led Boston’s Irish Ninth Infantry Regiment; General Thomas Meagher, who was part of the Fighting 69th before he formed and led the Irish Brigade of which it became a part; Colonel Patrick O’Rorke, who commanded New York’s 140th Regiment (and whose widow became a Sacred Heart sister); and General Philip Sheridan, who had charge of the cavalry of the Army of the Potomac. General William Rosecrans’ brother, Sylvester, was bishop of Columbus, Ohio.

Of course Catholics were active in the war in ways outside of combat. Priests served as chaplains on both sides. Fr. Abram Ryan not only supported the Confederate troops by spiritual ministrations; he also served the cause with his poetic creativity, penning paeans to the South such as “Conquered Banner.”

QuickQuote...

Of Sister Anthony O'Connell, SC:

"Amid the sea of blood she performed the most revolting duties for those poor soldiers.... She seemed to me like a ministering angel, and many a young soldier owes his life to her care and charity."

Eyewitness, Battle of Shiloh, 1862

Religious women played a major role in the conflict. More than six hundred sisters from twenty-one congregations made up some twenty percent of the nursing corps of the combined armies, North and South. They also managed other other war-related charities, such as assisting the families of wounded and deceased veterans.

The Civil War was a time of heroism and degradation, cooperation and conflict. Catholics, a growing percentage of the population in every region, participated fully in every facet of the event. The war, with its contradictory legacy of freedom and violence, remains both a scar and a badge of honor on the histories of the nation and of the Catholic people who call it home.

©2011 CatholicHistory.net. Posted February 1, 2011.

Photos, from top: P.G.T. Beauregard; Thomas Meagher; Philip Sheridan. Courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration (unrestricted).

Sources and Further Reading

Stephen J. Ochs, “A Patriot, a Priest and a Prelate: Black Catholic Activism in Civil War New Orleans,”U.S. Catholic Historian 12 (Winter, 1994): 49-75.

"The Civil War and Catholics," by Jon Wakelyn, in The Encyclopedia of American Catholic History

Judith Metz, SC, "In Times of War," in