Spotlight Archive

November is Native American Heritage Month, an appropriate time to take a look at the history of Catholicism among the indigenous peoples of the United States.

The earliest interactions between Catholic missionaries and Indians in the New World were not auspicious, demonstrating that both sides had much to learn about how to relate to the other. In the late sixteenth century, a group of Franciscans in Georgia were killed when their efforts to impose a moral code clashed with Indian values. Around the same time, Fr. Juan Segura and his Jesuit companions were massacred in Virginia.

The earliest interactions between Catholic missionaries and Indians in the New World were not auspicious, demonstrating that both sides had much to learn about how to relate to the other. In the late sixteenth century, a group of Franciscans in Georgia were killed when their efforts to impose a moral code clashed with Indian values. Around the same time, Fr. Juan Segura and his Jesuit companions were massacred in Virginia.

French missionaries were more successful among the natives of the St. Lawrence River Valley. The Hurons and Algonquians, peaceful and stationary tribes, were amenable to the Christian message and the lifestyle it implied. The Iroquois, however, were less so, and courageous attempts to evangelize them resulted in the deaths of Sts. Isaac Jogues, John de Brebeuf and their companions, collectively known as the North American martyrs. A few Iroquois did accept Catholicism—among them the “lily of the Mohawks,” Blessed Kateri Tekakwitha. [Update: St. Kateri was canonized October 21, 2012.]

French Jesuit Sebastien Rale worked very productively among the Abenakis of Maine. He, too, met an untimely death, however, when English settlers assaulted the Rale’s Abenaki village in the course of French-English colonial hostilities.

Yet another French Jesuit traveled far and wide without arousing the opposition of the American natives. Jacques Marquette not only successfully explored the Mississippi River by dealing respectfually and diplomatically with the tribes who lined the river; he also established lasting missions among the Illinois and Ottawa on the shores of the Great Lakes.

Father Eusebio Kino worked among the tribes of the southwest and gained the respect of the natives. His life exemplified the challenges missionaries faced: Despite his achievements and his sensitivity to native concerns, he met an untimely death at the hands of Indians.

Father Eusebio Kino worked among the tribes of the southwest and gained the respect of the natives. His life exemplified the challenges missionaries faced: Despite his achievements and his sensitivity to native concerns, he met an untimely death at the hands of Indians.

Possibly the most densely populated region of the United States prior to European contact was California. There, Franciscan friars led by Junipero Serra established a chain of missions in an effort to integrate Native Americans into Spanish culture—including its Catholic religion. Notwithstanding certain abuses and misunderstandings that sometimes led to violence on both sides, the friars sincerely cared for the Indians, defended their rights against the less scrupulous Spanish military, and succeeded in training many natives in skilled trades and agriculture—training that served them well during California’s transition from Spanish colony to American state.

As Americans moved west and encroached on Native American lands during the nineteenth century, Catholic outreach continued. By the 1820s, Catholic emphasis fell on the promotion of education. For Bishop Louis Dubourg of St. Louis, the welfare of Indians was a high priority. Frederic Baraga worked among the Ottawas and Ojibwe in Michigan, mastering their languages and publishing the first books in these native tongues. In the Northwest, Jesuit Father Joseph Cataldo worked among the Nez Perces and Spokanes, as well as the tribes of Alaska, while fellow Jesuit Pierre de Smet was a notable figure among the Coeur d’Alenes and Blackfeet, highly respected by the natives for his fairness and integrity.

By this time, the pattern of Anglo- and Native American interaction was set, to the lasting shame of Americans and to the detriment of the Indians. Sequestered on reservations scattered around the country, Native Americans entered into a period of economic dependency and social decline. A new wave of Catholic missionary activity, focused on educating and empowering Indians, began. St. Katharine Drexel devoted her fortune and the efforts of her congregation of women religious to the betterment of Indians and African-Americans.

At the Third Plenary Council of Baltimore in 1884, the Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions was recognized as an official Church agency, giving formal institutional support to Catholic ministry among the native peoples of America. Important figures in the Bureau included Frs. Joseph Stephan and William Ketcham.

At the Third Plenary Council of Baltimore in 1884, the Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions was recognized as an official Church agency, giving formal institutional support to Catholic ministry among the native peoples of America. Important figures in the Bureau included Frs. Joseph Stephan and William Ketcham.

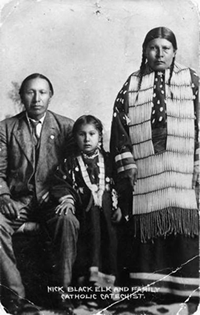

Over the course of the twentieth century, Native Americans acquired greater responsibility for their own affairs. One Indian catechist was Nicholas Black Elk, a Sioux holy man (and casualty of the Wounded Knee Massacre), who was baptized in 1903. Bishop Aloisius Muench of North Dakota established the Tekakwitha Conference in 1939. Originally a support group for Catholic missionaries, it thrived and grew as Native American Catholics themselves joined and directed the organization’s activities. In 1972, the Indian Education Act placed control of schools in tribal hands. Many Catholic schools continued in essence; they were sold to the tribes while many Catholic teachers and administrators remained, becoming employees of the Indians.

In the 1980s, two men of native descent were elevated to positions in the American Church's hierarchy: Donald Pelotte as coadjutor bishop of Gallup, New Mexico; and Charles Chaput as bishop of Rapid City, South Dakota. (Chaput later became archbishop of Denver and then Philadelphia.)

The legacy of Catholic missions among the Indians is clear in the thousands of devout American Catholics of native descent. Catholic parishes are still active on the reservations of the United States, but many more Catholic Indians have assimilated into American society, indistinguishable from other Americans. Along with America’s millions of immigrants, they have experienced the melting pot: the loss of a distinctive identity rooted in a long and noble history, but the gain of forging a new people, both American and Catholic.

©2011 CatholicHistory.net. Posted November 2011.

Photos from top: Jesuit Missionary instructing the Indians; from a c. 1885 engraving, Illinois State Museum, Springfield, IL, courtesy Wikipedia; Pierre De Smet, SJ, courtesy Washington State University; Nicholas Black Elk with wife and daughter, courtesy Wikimedia Commons (public domain)

Sources and Further Reading

C. Vecsey, The Paths of Kateri's Kin