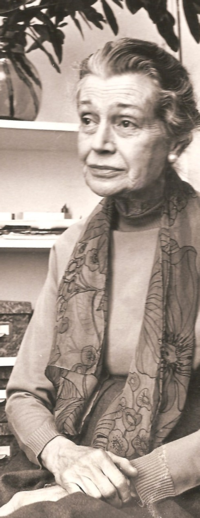

Marion Mitchell Stancioff (1903–1996)

Marion Mitchell Stancioff (1903–1996)

Marion was born in Sao Paulo, Brazil on August 8, 1903, to a Protestant family. Her father was an engineer and businessman involved with the development of hydroelectric power. Her childhood was spent in the United States, but in 1908 the family moved to London, England. She attended boarding school and graduated in 1922.

From the time of her youth, Marion studied wood engraving with Leon Underwood. She would later become one of the founding members of the British Wood Engraving Society. She met her future husband, the son of the Bulgarian minster to London, at a charity ball for Russian refugees in the Hyde Park Hotel. She and Ivan Stancioff were married at the Brompton Oratory in London in February 17, 1925. Unusual for a Bulgarian (who were mostly Orthodox), Stancioff was from a Roman Catholic family. Marion became interested in her husband's faith and converted.

Subsequently, she found herself living a diplomatic life and was soon raising her seven children in Sofia, Bulgaria. The Papal Visitor to Bulgarian during this time (1925-1934) was Bishop Angelo Roncalli, later to be Pope John XXIII. He was often a guest at the Stancioff table. When he became Pope, he gave the family a private audience in Rome (January 31, 1961), recalling their earlier friendship in Bulgaria before the war.

During World War II, Marion saw her husband assigned to diplomatic duties in Albania. Bulgaria remained neutral as the Axis powers invaded Yugoslavia and Greece. Marion was traumatized by the railcars filled with human beings who were being sent back to Germany (Jews bound for the extermination camps). She and her husband, although legally they could do nothing about the souls traveling through their country, were active in helping as many as possible both diplomatically and personally to escape from the Nazi turmoil. The Bulgarians joined the Axis powers in 1944. Marion, because she had been closely involved with these kinds of activities, was advised to take herself and her children abroad.

Marion and her seven children went to live in simple quarters in Switzerland from 1943 to 1946. The war was over in Europe in 1945, but there was nothing to go home to in Bulgaria, as the communists had moved in and all their belongings and monies were confiscated. As the daughter of a businessman father and a Baltimore socialite mother, who was at this time a widow living in Tuxedo Park, New York, Marion decided to move to the United States. With the financial help of her mother, Marion brought the family to New York to live with their grandmother in Tuxedo Park. Eventually, they bought their own place outside Washington, D.C. in Frederick, Maryland. Because of the family’s involvement with the diplomatic core and their proximity to Washington, the Stancioff home welcomed many international and diplomatic visitors. Marion would often visit Ezra Pound at St. Elizabeth’s hospital. She had known the Pounds in Italy, before the war. Father Ivan Illich was a frequent visitor to her home, as was Anne Fremantle, to mention but a few. She was a personal friend of Dorothy Day, Maisie Ward and Frank Sheed.

Marion never hid her Catholicism. She took her faith very seriously; however, she did not see her faith as limiting her involvement with the modern world. Instead, it impelled her forward into the mainstream of society. She was totally dedicated to Catholic Action. She believed that everything was useable to glorify God.

Marion had long been writing about the faith in her personal journals. The journals portray a very humble and obviously faithful Catholic who sought communion with the spirit of God. Her prayer life and daily reception of the Sacraments were marked by all her children in interviews conducted with them in 2008.

She was a journalist before returning to the United States. While living in Switzerland, she began writing for the Catholic press. Ultimately she would write for Commonweal, America, Sun Herald, and National Catholic Reporter.

Marion had sought out the editors of Integrity Magazine while on a trip to New York. She made friends with Carol Jackson. Her first article appeared in October of 1948: “Is Communism Inevitable?” This would be one of several articles written on Communism for Integrity. Marion would also write on topics pertinent to women: “The Love-Education of Girls” (1949) and "People are People are People," part of a September, 1953 issue devoted wholly to "woman." Stancioff argued that both history and Catholic doctrine suggested that gender is an earthly principle rather than a heavenly objective. All told, she wrote twenty articles for Integrity, up to the publication's last issue in 1956. The bulk of her articles dealt with family, the practical guidance of children, and maintaining a healthy Christian perspective on everyday reality.

When Integrity closed its office in 1956, Marion went on to write for the Kansas City Sun Herald and the National Catholic Reporter.